Normally, I look forward to writing these newsletters. They offer a chance to step back, take stock of what we’ve built together, and celebrate some specific examples of the work we’re doing. But this week, instead of reflecting on progress, I find myself writing about the projects now at risk of being shut down—and how we can support the staff and trainees whose jobs may disappear with them.

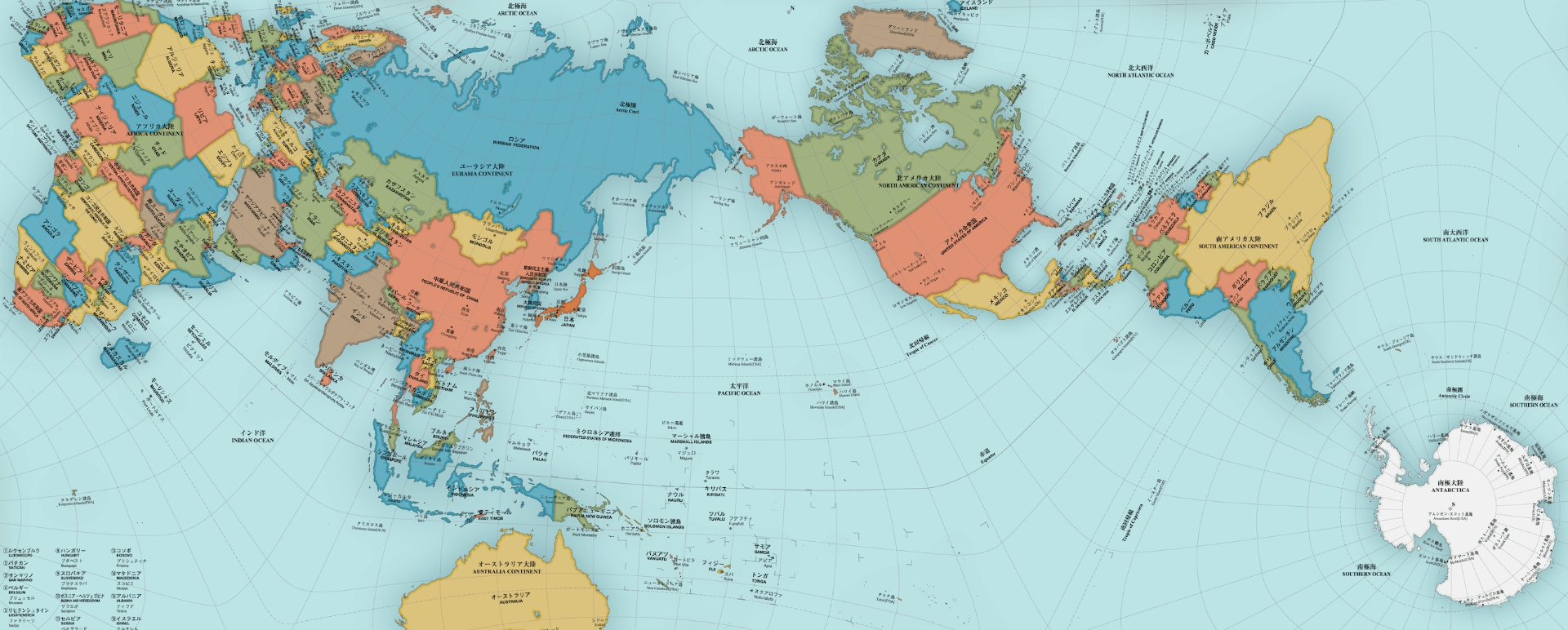

As many of you know, the federal government has informed Harvard that it will freeze $2–3 billion in grant and contract funding, much of it from the NIH. We don’t yet know when or how this will roll out, but we’ve been told to expect stop-work orders on all our NIH-funded studies. That includes the grants that fund our faculty, trainees, and staff here at Harvard—and those that support collaborators in Peru, Rwanda, Madagascar, Guatemala, and Lesotho, among other places. While Harvard may be able to absorb some immediate losses, the partners we work with abroad cannot. Fieldwork will stop abruptly. Promises we made to participants—that their involvement would lead to new knowledge and better care—will go unmet.

Paul Farmer created our global health research core in 2010 with the goal of expanding the department’s work to include more field-based research on delivery and impact—work grounded in epidemiology and biostatistics. That was new for the department, which had long focused on the social sciences. Over time, our small team became successful at securing NIH funding to support this mission, and today, most of the core’s work—and the people who do it—are sustained through those grants.

Here are just a few of the projects now in jeopardy:

- Molly Franke leads a clinical trial in Peru designed to help adolescents with HIV stay in care as they move from pediatric to adult services. She’s also studying how social media can reduce HIV stigma among teens. In another project, she uses advanced causal inference methods to evaluate the effectiveness of new drug regimens for multidrug-resistant TB—work that allows us to answer critical treatment questions even when clinical trial data is not available.

- Bethany Hedt-Gauthier is leading a study in Rwanda that supports community health workers in providing at-home follow-up for women recovering from cesarean sections—especially important in rural areas where traveling to a clinic is costly and difficult. Her team is building and evaluating a decision-support tool that could change how postpartum care is delivered in low-resource settings.

- Ann Miller works on several NIH-funded studies, including a multi-country project to evaluate early child development interventions in rural Guatemala and India. Her work supports community health workers in delivering individualized support to caregivers of young children. In another study, she’s investigating the relationship between aflatoxin—a common food contaminant—and child growth and whether the gut microbiome plays a role. She’s also part of a study aimed at addressing the “double burden” of malnutrition in Guatemala, where mothers are overweight while their children are stunted—a growing challenge in many rural areas.

- Letizia Trevisi supports several of the projects mentioned above and also contributes to a study aimed at improving nutrition in the Navajo Nation. That team is exploring culturally grounded, strengths-based strategies to promote healthy beverage choices in early childhood—a simple intervention that could reduce chronic disease risk and support long-term health in Indigenous communities.

- My own work focuses on tuberculosis. One study in Peru is investigating bacterial genetic factors associated with failure to respond to TB therapy. The other looks at how both host and microbial factors contribute to long-term lung damage after TB treatment – the goal is to find ways to prevent this post-TB lung impairment.

All of these projects are likely to be cut off mid-stream. Some are just getting underway. Others are years in the making. The time and funding already invested may be lost—but the real loss is to the communities we work with, and to the staff, students, and collaborators who have made this work possible.

We’re doing everything we can to advocate for this research and protect the people behind it. In the meantime, we’re also exploring ways to diversify our funding to keep projects afloat and teams intact. If you’re in a position to support this work—or if you have ideas about where we might turn for support—I’d be grateful to hear from you. Please feel free to reach out directly. I’ll continue to share updates as we learn more.

Best,